Once upon a time, many decades ago, when I was a little girl, our summer holidays alternated between the cousins coming over to stay with us, or we going to the village to stay with them. So, every other year, my brother and I would be packed off to the village to stay with my uncle and his family. The train journeys need a separate article of their own, but for the time being, let’s suffice it to say they were memorable, with the hot, balmy breeze blowing in our faces as we sat with our cheeks touching the iron bars on the window, eager for the train to arrive at a certain station where we’d buy cups of piping hot chai, to be had with the puri-bhaaji mother would have prepared and packed for us. We’d arrive in the village, dirty, grimy, and stinky from our long train, but no one seemed to mind back in those days. A quick shower with soap would take care of it all.

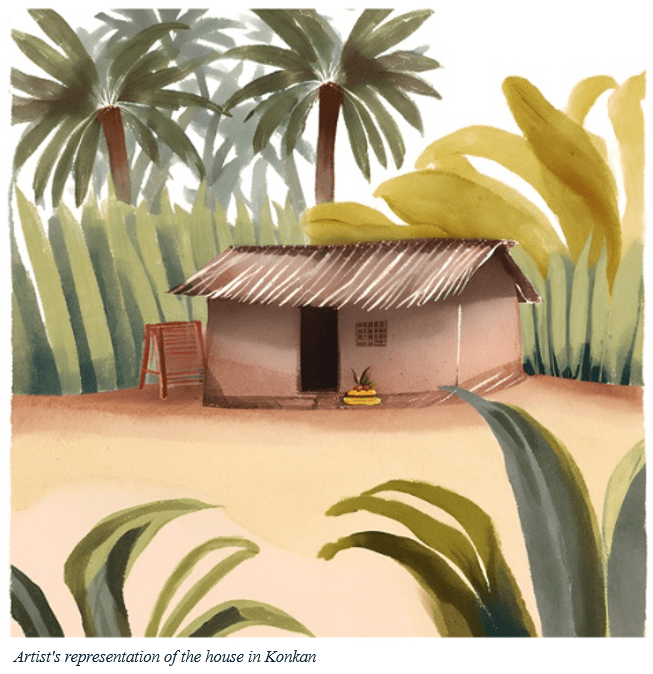

Uncle’s tiny house, a traditional, village-home in konkan (coastal Maharashtra) was always pleasantly cool. The kitchen, located at the back of the house, was the only place one might find some heat, and during the occasions we were in konkan for Diwali, everyone tended to gather around the chul, a fireplace used for cooking. It had two big windows, and a door that led out into the backyard, where one could access all the ingredients required in daily cooking. My aunt always left the windows and doors open while the chul was fired up to prevent accumulation of smoke in the house. In a corner, there’d be a neatly arranged stack of cowdung cakes. It used to be my job to bring her the cowdung cake to fuel the fire. On other days, I would love going with her to gather the cowdung, and she merrily taught me how to pat it into perfectly round discs of same diameter to be laid out in the sun to dry.

My aunt had exactly two cooking pots, each of them earthen, and one iron tawa, on which she’d make the yummiest and lushest bhakris, from whichever crop was in season then. Being summer, I remember us eating ragi bhakris the most. Her cooking was simple and efficient, made using the least possible ingredients, and yet, the taste of it still lingers in my memories, years after I’ve had it. The earthen pots were chipped and old, but aunt never spilled a drop from them. The aroma of coconut curry cooking in those pots is akin to a whiff of heaven on earth.

My cousins, uncle’s children were both boys, and closer in age to my brother than to me. I’d thus, often be left to fend to my own source of entertainment. Luckily, I was easily amused, and found joy in things to do around the house. It was almost meditative to use the vili (a curved knife used to chop vegetables, with a rounded scraper at the end for coconuts), and aunt let me, albeit keeping a watchful eye lest I accidently cut myself. We’d chat while she went about her daily household chores, me following her around like her tail. Even today, I attribute the success of my thriving kitchen garden to the conversations I had with my aunt, who was an avid gardener, and had a kitchen garden of her own despite living less than a hop away from the farm. She said she wanted uncle to focus on the yielding crops, while she’d take care of the family needs. I also spied her generously handing bunches of greens and vibrant fruits to the neighbors in exchange for a bowl of sugar or salt. She said she rarely went to the market to buy these things, teaching me a life lesson about prevalent barter systems in the society.

It was mesmerizing to watch my aunt work at the chul while sitting on the hard, stone floor. She’d give me the signal, and I’d happily jump to my feet to fetch the thickest banana leaves for mealtime – ‘setting the table’ as one might refer to it in today’s times. However, back then, there was no table. I’d roll out the straw mat along one wall of the kitchen, and clean, cut, and place the banana leaves before the assigned spot of each individual. My aunt would then serve us all half a bhakri each, along with a side of coconut chutney. There would then be a generous helping of rice, topped with amti (dal, lentil soup). Other days, she’d make the most luscious, scrumptious coconut dosas. The last day of our stay always had us eating ekpani tambali, a curry made using the brahmi leaves, which grow in abundance during monsoon. At the end of each meal, my uncle would gather all our ‘plates,’ the banana leaves, and feet them to the cows and goats in the farm. It would be my brother’s job to sweep and mop the kitchen, while my aunt would wash the utensils in the small nhanighar, just off the kitchen.

At night, once the kitchen had been cleaned and swept, we’d roll out the cotton mattress and spread a faded old cotton sheet on it. The stone floor would still be warm from the still-cooling chul, and I usually fell asleep the moment my head hit the pillow, safe and cozy in the warmest part of the house. My uncle and aunt usually slept in the front room, leaving us cousins to giggle and share scary stories on the rare occasions we did manage to stay awake in the dark of the night, for mornings begin at the crack of dawn in konkan, and the kitchen fires are lit not just to cook, but also to warm up the human system with a cup of chai.